Turning Dreams Into Reality

By: Martin Váša

Photo: Shotby.us

Marek may be turning the dreams of others into reality, but his profession is not his dream come true. Certainly not as much as it was for his father who, unlike his son, was always fascinated by glass.

“We have a cottage in the Gratzen Mountains. When I was fifteen, my father read somewhere that there was an abandoned 17th century glass melting furnace in the nearby Terčino Valley. It had no protection against rain and was overgrown with nettles, so he took me there to clean it and cover it with a roof. While doing this, I found a crucifix pendant. My dad told me then that it was a sign. That I was now under an obligation to become a glassmaker.”

Part of the deal was that the first choice secondary school would be up to Marek. If not accepted, he would train to be a glassmaker, to comply with his father’s request. “I do not even know why, I chose a secondary school of construction,” he laughs. “And I ended up eleventh among those who did not get in…” The future was decided.

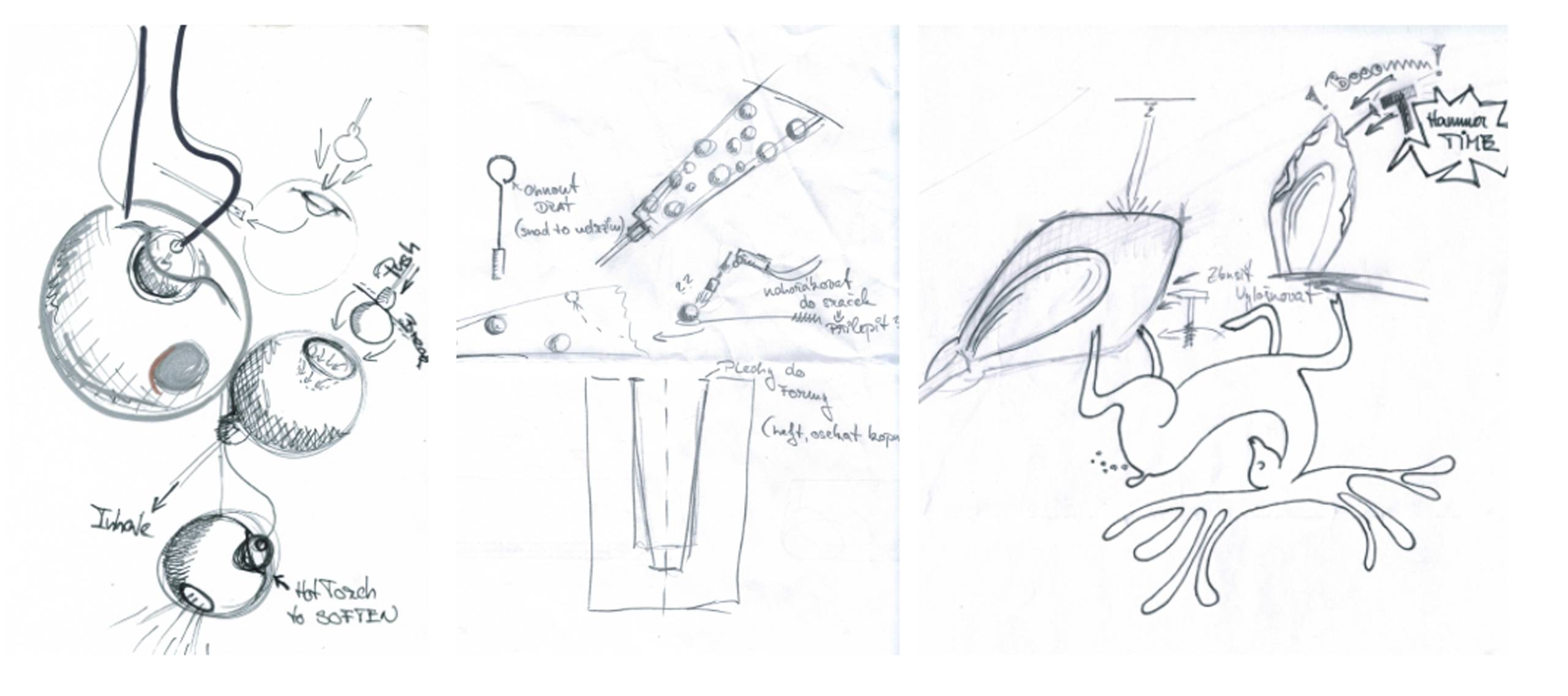

It is Marek’s responsibility to prepare the design for the legendary Salone del Mobile design fair in Milan. It all starts with a design pitch, totalling some sixty proposals. From these, the Art Director selects the top twenty. “Maxim Velčovský makes sure the item looks good and is aesthetically attractive. I look at it from a craftsmanship point of view; if it is going to be a challenge for me to make it – if it is something that has not been done before.”

At that time, glassmaking struck him as a craft that is passed on from generation to generation. He would never have imagined that he would be able to do something like this professionally one day. His father took him to the glassworks in Světlá nad Sázavou, where he asked the foreman whether his son would be capable of working with glass. The foreman grabbed a broom and threw it at Marek. He caught it, the glassmaker continuing to look at him with inquiring eyes. “He can hold the broom just fine. He will be ok!”

“Once you get too confident, the glass will punish you. A humble approach to glass is the most important thing!”

Marek also specializes in making the object easy to produce in the glassworks and ensuring that the glassmakers know how to create every little aspect of the object. That’s why he often explains the details right in the glassworks – through his own chalk drawing directly on the floor.

LEERDAM IS TO THE NETHERLANDS WHAT NOVÝ BOR IS TO THE CZECH REPUBLIC

Upon completion of his studies, he was expected to start working in the glassworks his father had established in the meantime in their home village of Hrdějovice. It only took Marek six months at school to fall in love with the craft of glassmaking but, after finishing further education in Nový Bor, he was interested in going to places other than southern Bohemia. Next stop: Leerdam, The Netherlands.

“I went to The Netherlands for a study visit and stayed for four and a half years,” he says. “It was an amazing experience, I could practice glassblowing every day, spend time in the glass-cutting workshop, melt glass… I learned a great deal there.” He found his niche in a studio collaborating with the National Glass Museum in Leerdam. When some of the exhibiting artists wanted to use glass, it was very likely they would join forces with Marek at some point. “Suddenly I was not just creating my own stuff and playing with glass, I was making things for other people and the result had to be up to standard.”

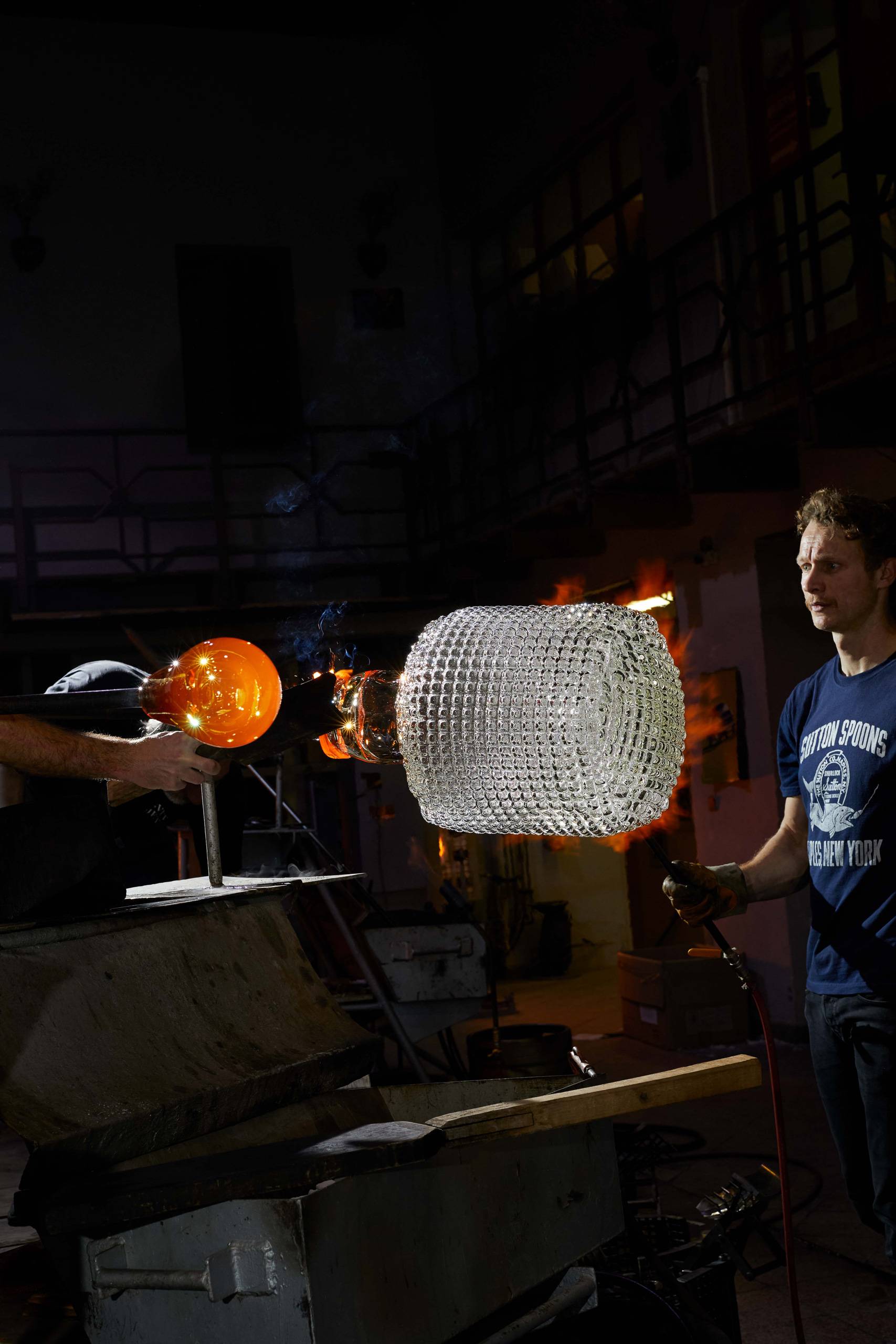

Proper timing is the alpha and omega of everything. “If we open the mould too early, it affects the shape of the glass inside, but if we open it too late, it ‘freezes,’ as we say, and it becomes impossible to get it out.”

WHEN WORKING WITH GLASS, PILCHUCK IS A MUST DO

Then Marek was awarded a scholarship to expand his knowledge at the prestigious summer course at the mecca of glass – the Pilchuck Glass School. Out of the three hundred participating students, he was the only one from Europe. “It changed my life,” he says, clearly not exaggerating. “There, I saw things made of glass that I did not even know were possible.” So, he spent three weeks deep in the woods, a two-hour bus ride from Seattle, in a community of fellow students, working from morning till night at the glassworks. He happened to be taught there by Jiří Harcuba, one of the greatest glass engraving experts, originally from Bohemia. “I never thought for a moment that I should be anywhere else, this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity!”

“There is nothing in our range now that is more difficult to make. Dune is a symphony performed by five glassmakers working on one piece!”

His visa for the United States was not due to expire until a year and a half after the end of the course. He intended to spend this time as an assistant in the studio of artist Leon Applebaum. “I went there with the idea that I could earn some extra money and visit Corning at weekends, which is twenty minutes away, and where the most beautiful glass museum in the world is located.”

But then his phone rang. Martin Janecký, a renowned artist specialising on the ‘inside bubble sculpting’ glass-shaping technique whom he barely knew, offered him a work trip to Alaska. Three weeks later, Marek was on his way. He and Martin spent three winters in Alaska, sculpting “inside the bubble” and skijoring (in which Marek also won the gold medal for Alaska), before they both returned to the Czech Republic.

NOTHING IS IMPOSSIBLE: FROM JAN KAPLICKÝ TO ZAHA HADID

“I was really looking forward to this job, it was a huge challenge for me,” says Marek, and even today, after more than seven years as a developer, you can hear the enthusiasm in his voice. “Designers come up with an idea that no one has ever tried before, and I have to work out how to make it attainable,” he sums up his current job.

“The moment when you put glass in the mould is the most difficult and most important one. The mould must be perfectly composed. For making Hidden Light, for example, it consists of nine parts which must meld together perfectly, otherwise it shows on the final product. The glassmakers must recognize that special moment when it is necessary to close the top and enclose the bubble. After that, all it takes is controlled blowing. Then you open the mould and take out the finished product from its cage.”

Although the label in the store does not bear Marek Effmert’s name, he has played a key role in the production of such iconic objects as the Cooler designed by Jan Kaplický or the Eve and Duna lightings by Zaha Hadid.

Marek was making the Cooler shortly after Kaplický’s death and was sorry they had not met. Especially since he was the first one who succeeded in devising a method for making the product to exactly correspond with the design. “The Cooler is supported by two feet that must look like they are made of the same piece of glass as the rest of the vessel, but they cannot in fact be attached in any other way than by sticking them on. They cannot be made by pulling on the glass because it would deform its shape of the cooler. But I brought a lot of tools from the States that nobody knew here, including an oxygen torch. I used it to heat the body of the Cooler and then attached molten glass feet to it. They bonded so perfectly to the heated surface that it is impossible to tell they were attached at all.”

“I never wanted to be seen much. I prefer my work to be seen.”

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD, AND THE WORD WAS NO

There is a Czech saying suggesting that people often end up doing what they initially rejected, and it is most definitely true in Marek Effmert’s case. He is lucky he learned to love working with glass, and Czech glassmaking is extremely lucky he did. Effmert is considered one of the brightest stars of the glassmaking industry. His expertise and skills as well as his achievements are simply unmistakable and truly unique.

At secondary school, he was lucky to be in the class with students who were genuinely interested in the field, and yet today he is the only one of his classmates who is professionally involved in glassmaking. “After my generation, there are no more glassmakers here,” he says. Marek does not have to brag about anything, does not need to be seen. To be happy, all he needs is to accomplish another extraordinary task – to make another dream come true.

After taking Hidden Light out of the mould, it is still necessary to put a torch to it, and to line the lamp neck with a thin string of fresh glass which, like the torch, returns the necessary temperature to the glass product.

Marek Effmert comes from České Budějovice. He completed training at the glassmaking school in Světlá nad Sázavou and continued his studies in Nový Bor. He also spent some time gaining experience in the glassworks built by his father in his home village of Hrdějovice. During a study stay in Leerdam, the Netherlands, he had the first opportunity to give material form to the visions of other artists. He is still doing this at Lasvit, where he has been a member of the Research and Development team for over seven years. In addition to what he learned in Leerdam, he also continues to build on the experience gained at the Pilchuck Glass School and on his long-standing collaboration with glass artist Martin Janecký. His name is associated with the brand’s iconic pieces such as Jan Kaplický’s Cooler, Zaha Hadid’s Duna and Jan Plecháč’s new Hidden Light. He also participates in the development of custom-made projects. He has been part of the Lasvit family since 2015.