On Creating Sense of Intimacy

By: Eva Slunečková

Photo: archive

Subject 1: Home

Home should interest you in being there more than just being in a house. Home should inspire you, make you grow, give you something, you’ve imagined, which is not just given as a ready-made. Good intimate space that we know from history is more than described by our words – it’s created by beautiful light, proportions, a connection to nature, to the stars. That’s the beauty of humanistic design. There is no formula for creating “a home”, it’s made to measure. When Heidegger says “the center of the home is a heart”, it is connected to the more primordial forms of dwelling, not to the modern urban world, where people rush to feed their families, to go to work… How can we accommodate these hardworking people in a world exposed to all types of media today and make sense out of it? There are many strategies of design, one of which I use is to never do just the ready-made, never just copy what has been already done. You have to tailor each situation to a physical as well as a cultural context.

“Bauen originally means to dwell. Where the word bauen still speaks in its original sense it also says how far the essence of dwelling reaches. That is bauen, buan, bhu, beo are our word bin in the versions: ich bin, I am, du bist, you are, the imperative form bis, be. What then does ich bin mean? The old word bauen, to which bin belongs, answers: ich bin, du bist means I dwell, you dwell. The way in which you are and I am, the manner in which we humans are on the earth, is buan, dwelling […]. The old word bauen, which says that man is insofar as he dwells, this word bauen, however, also means at the same time to cherish and to protect, to preserve and to care for.“

HEIDEGGER, M. Poetry, language, thought. London: 1971

For me personally, a home is about a good book. Actually, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was already saying, that a gentleman shouldn’t own more than six books. Which I haven’t succeeded so far! (laughing) But anyway, I believe home should be full of things that I love, which is books, music and a game of chess. That’s my true center of an intimate space but, in general, today’s home is a very fluid concept. For many people it just means to have a phone or a tablet in their hands. It doesn’t have to be about walls or a certain space anymore, it’s a question of connection embraced by all kinds of reality today – physical or virtual.

Subject 2: Luxury

It’s not a question of money anymore. For me, luxury is the intimate connection with people, it’s a question of culture. Sometimes that can be accomplished by very humble means, simple materials or forms. Luxury is taken as a commodity, but originally luxury is about building a particularly intimate environment and to create the right connections to it. Especially when the planet is suffering the notion of sustainability and what is beautiful is no longer taken for granted, that beauty is exploitation. Now beauty can be something really humble, down to Earth or communicated more spiritually.

Subject 3: Uniqueness

Even when you’ve a massive block of people living within a certain economy of scale, a certain economy of construction, a certain necessity in terms of how transportation systems work, still even in this large scale, with hundreds of units, you can create a sense of uniqueness. By shaping the entire project in a way, which is not formulating but really relating it to the earth and to the sky, to the sense of who is gonna be living there, to the context of the neighborhood and most importantly, to the human scale. And not just physical scale as Le Corbusier has always said “the ideal Frenchman is 1.76 centimetres.” That is not true, because true human scale is not just a height of a person, it’s the height of their aspirations and dreams.

For example, when we’re speaking about office buildings, there are many options for how we can deal with them. Every floor can work with slightly different positions and creating the space. Thousands of people can work in such a building but when you go to such a space, every new floor you’re in is a slightly new neighborhood, which is completely different from the floor above you and below you. I think this has a very big impact in giving you a sense of different context, that you’re not part of something huge but you’re an individual. That uniqueness in the context of the structure has such a huge impact on how you perceive the whole. You can customize everything from a small to a huge scale and it will have a big impact on people using the space.

Subject 4: Symbol

There is nothing in the world that is not symbolic. Even a blank wall, as Leonardo da Vinci recommended to artists — go and look at a blank wall because if you sit in front of it more than 3 minutes, you will see the most amazing paintings ever imagined. We can’t escape meanings, it’s just a sense of being sensitive to it, to engage with it and create out of it.

Subject 5: Identity

Not only in museums or memorials is it possible to create a sense of privacy, even in a social housing project or a residential development. Each window is slightly different, each place has its own identity. It’s not just a bunch of rooms of the same kinds repeating themselves. It is about trying to find uniqueness by the uniqueness of space by the uniqueness of the person who will be living there. Customizing is giving you a sense of place, it’s telling you that you aren’t just a number, a statistic, but an individual, a human being.

Subject 6: Privacy

In history, the public space didn’t have such a huge border of privacy — in European cities the piazza used to be a kind of living room, where people lived. Today there is a huge border between private and public spaces. It’s causing contradictions – we either seek to escape home or seek unlimited possibilities in the common space. Since the 19th century, we’ve already known, thanks to Edgar Allan Poe and The Man of the Crowd, that the best way to see privacy in a modern city is to be inside of a large crowd. Today, in the pandemic, we’re realizing, that private space must also be a shared space and these two worlds have to be much more related. Home is not only about yourself anymore, but is also a social space.

“He refuses to be alone. He is the man of the crowd. It will be in vain to follow, for I shall learn no more of him, nor of his deeds. The worst heart of the world is a grosser book than the ‚Hortulus Animae‘, and perhaps it is but one of the great mercies of God that „er lasst sich nicht lesen.”

Edgar Allan Poe, The Man of the Crowd, 1849

The cell of a prisoner is not so different from the cell of a saint. Both are similarly closed environments, yet for the saint it is a transcendent environment, which stretches out of the place and goes beyond the worlds, while for the prisoner it’s just a horrible misery. But we must really study the difference between those two environments. It’s not just about the physical environment, but about what we bring to it and what the experiences and design is about. It must be based on experiences and not ideology. We need a sense that we are connected to the world around us and its beauty. Also, what are we looking at, which kind of daylight and what does its quality have, how much nature are we able to bring in, that’s one of the important tasks of contemporary architecture.

When you look at the etching of St. Jerome and his study by Albrecht Dürer, you can see a lion, books and all the things that surround Jerome of notions that go way beyond the little cell he’s sitting in. That is what is making a space an intimate space. The moment when you’re surrounded not just with material objects but with things that give you a sense of need.

When I worked on the Dutch Holocaust Memorial of Names, which is a public space on a completely open piazza, I designed it in a way that people can find intimacy in reading a singular name on a brick of someone, who was part of the city and was murdered as a result of inconceivable events that we’re reinspecting today. In the center of a great public space I created a sense of privacy with a singular name, singular date, singular age of each person. On the other hand, in the Jewish museum in Berlin I made the void by creating the holocaust tower. Anyone can enter and have a sense of one’s self, because you find yourself in a situation that is not an obvious one, in which you haven’t found yourself before.

Subject 7: Connection

If people are suddenly connected with something that is not just about the functionality or aesthetic of design, but something that has a deeper layer of meaning, they’re often surprised, shocked, that it’s driving emotions beyond the daily idea of the function. The cultural dimension is so important because it represents the spiritual dimension of architecture that is not really a theme today in design. During the pandemic, people rediscovered their mortality, which had been suppressed among the society for decades. By seeing the limits of human hubris, of control, people opened up to a more philosophical sense, such as what it means to have an identity or a personal space. Design should be holistic, it’s not just about the glossy polished reality, but also about the gap in reality. To fill these gaps with the facts that caused them in the first place — we’re looking at the world as it is and not as a kind of illusion such as on the internet, TV or mass media — by doing that we’re returning to a sense of humanity, that is really the center of it all — the people’s normal lives.

Subject 8: Atmosphere

People are far more creative then they‘re given credit for. We are usually trapped in repeating the same thing all over again because what you like, is given to you, and what you don‘t like, is taken from you. In my mind we have to extend this world and give rid of this idea of that bubble. We should open to new ideas, new design, new materiality, new sense of intimacy, new sense of connection to individual living. Intimacy doesn‘t have to be something fragile, some sort of a cloud, it can be very bold and connected with strong geometry.

Subject 9: Spiritual linkage

A person doesn’t just have a body, man has a soul. And a soul isn’t something, that is banal or a metaphor, it’s a reality. You have to connect yourself to the spirit of a place, a genius loci, that’s irreplaceable. It isn’t the same place anywhere in the world because it is just there, on this particular spot. You have to imagine yourself in a sense of what is required by a person, whatever their age, whatever their religion, whatever their race, whatever their gender. How to create a space that is not just comfortable in a sense of comfort coming out of a commercial commodity, but is the spiritual linkage of the space you’re designing to any dweller in a city or any dweller of a home. I think imagining a connection like that is stronger than any kind of knowledge and help in the areas of designing that are not so obvious.

Subject 10: Direction

People underestimate memory. What is the design tool that you need the most? It’s not really your ruler, a compass or geometric paper. Memory can’t be accessed by a computer, memory is much deeper. That is the ultimate dimension of design, a true guidance in life. So if I could design whatever was possible, I would love to build a house just out of the poetic consciousness of people.

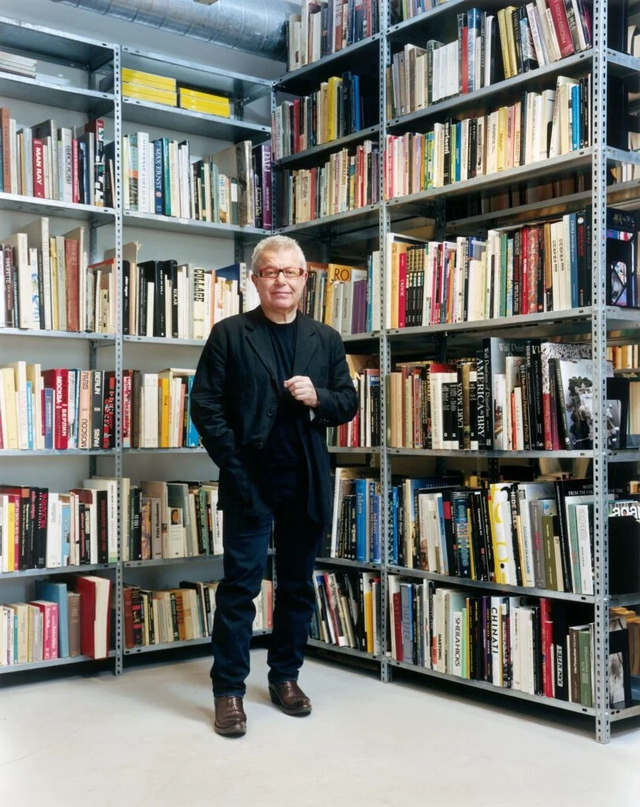

Daniel Libeskind. An international architect and designer of Polish-American origin, links the emotional charge of architecture with philosophy, art, literature and music. He embraces the notion that buildings are crafted with perceptible human energy, thus addressing the wider cultural context within which they are built. Libeskind established his architectural studio in Berlin in 1989. He is best known for the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the master plan of the World Trade Center in New York. He is the author of several residential and public projects and also a product designer. Libeskind is also part of the Lasvit family since 2014 with chandelier Ice and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern objects for the Monsters collection.