The Elusive

By: Mariana Kubištová

Photo: Richard Bakeš, archive

The life of Bořek Šípek was the story of an artist who, being hardworking and courageous, rose from humble beginnings to international fame. In particular, he did not lack the courage to cross borders – both the geographical ones, when he emigrated from Czechoslovakia to West Germany at the age of 19, and 15 years later moved to the Netherlands; and the ones that could limit his work.

Relatively early on, his talent and enthusiasm brought him his first professional successes. One of his early awards in architecture was the German Architecture Prize in 1983. Šípek received it for a house called Glashaus that he designed for his sister Stanislava. A number of other architectural assignments followed shortly. Instead of the anonymity of modern architectural trends, Šípek always opted for an individual approach.

This was the way he worked on both large buildings and interior designs which he carried out all over the world. Whether designing the Komatsu Ginza department store in Tokyo, the Škoda Auto pavilion in Wolfsburg, or the interiors of the Schoebaloo chain of shops and Karl Lagerfeld boutiques, Šípek was always successful in finding the right balance between luxury and functionality, between the intimate and the public.

“I want people to fall in love also with the objects that surround them, to really feel their presence as a physical challenge. I’m only interested in making objects with which we experience special moments, even on an ordinary day.”

He also had a unique opportunity to put his experience with “great” architecture and interior design to good use in a place with countless historical references, symbols of power and grandeur – Prague Castle. In 1990, Václav Havel, the Czech President at that time, appointed him the chief architect of his official residence. It is clearly evident now how good a decision this was. Fully aware of reciprocal relations between interdependent objects, Bořek Šípek managed to add both larger and smaller architectural elements and furnishings such as chairs, carpets and lighting fixtures to the existing architecture, which is itself a mixture of different historical styles, without disturbing the spirit of the place.

His designs accurately capture what is especially important in places like this – a sense of magnificence which, however, is not exclusive. Etched in the memory of Czech citizens is, above all, the office of Václav Havel from which he delivered his presidential speeches; but Šípek also designed the entrance to the Office of the President, the interior of the Prague Castle Picture Gallery and many other elements.

Function is the beginning, not the objective

If you don’t know how to start anew, you end up being in a rut. I don’t like to be restricted. By anyone and by anything. I like to try new things, new materials, new principles, new methods.” The approach to creation that Bořek Šípek applied in all areas of his activity is particularly evident in his product design. His unique ability to handle different materials and employ functions of objects has attracted the attention of many renowned companies, with which he subsequently collaborated. The first to approach him, in the mid-1980s, was the Italian company Driade, for which Šípek was designing various objects until his untimely death in 2016.

Driade provided him with media support and created a catalogue for him, featuring exclusive collections produced in limited quantities. Afterwards, he was approached by other well-known manufacturers, for example Alessi, Rosenthal and Vitra. In spite of their extraordinary and playful shapes, his pieces of furniture as well as glass, porcelain and metal tableware and other objects are highly functional and practical. In the 1980s, Šípek’s skills earned him an indisputable place among leading designers, such as Philippe Starck, Ettore Sottsass, Ron Arad and Oscar Tusquets, who were also his friends.

Šípek’s objects often have a symbolic meaning and their shapes and names refer to past personal experiences. For instance, the shape of the Bambi chair, named after Šípek’s first wife, the dancer Bambi Uden, alludes to the seated position of a dancer with legs apart. It is also a suggestion of the erotic aspect of Šípek’s works, and it is clear he did not perceive eroticism only in its most obvious sense, but rather as a relationship between man and object.

“I want people to fall in love also with the objects that surround them, to really feel their presence as a physical challenge. I’m only interested in making objects with which we experience special moments, even on an ordinary day.” The names of many of the objects also hint at real-life stories – they often suggest friends and colleagues of Bořek Šípek, or historical figures.

In his lifetime, Bořek Šípek realized a number of important architectural projects around the world. He implemented many of them, but some remained only in draft. The second group includes, among others, the project study for the Doha Bank Building in Qatar from 2004.

“The essence of architecture is not objective truth, but captivating radiance.”

The joy of creation

Bořek Šípek’s work is full of joy, which is also experienced by the viewer. That is why he also preferred Buddhism to the European Christian tradition. While Jesus suffers on the cross, the Buddha is calm and smiling, embodying the state of mental and emotional balance. There is no suffering in Šípek’s work, on the contrary – his art is a joyful part of life. What gave Bořek Šípek the greatest pleasure and also respite was his activity as a glassmaker.

“If you don’t know how to start anew, you end up being in a rut. I don’t like to be restricted. By anyone and by anything. I like to try new things, new materials, new principles, new methods.”

In 1982, Šípek built the house called Glashaus in Hamburg. A delicate glass structure – a greenhouse – conceals the actual dwelling. Like many of Šípek’s other works, the house is a collage – a combination of different approaches and materials.

He was introduced to glass by the most competent. After the untimely death of his parents, the famous Czech glassmaker René Roubíček became Šípek’s guardian. He and his wife Miluše Roubíčková, also a glass artist, had a formative influence on Šípek’s attraction to glass, which first manifested itself in a series of designs in the 1980s and was fully brought to fruition with the establishment of the Ajeto glassworks.

Bořek Šípek founded it in 1991, together with the master glassmaker Petr Novotný and the specialist in technology Libor Fafala, so that he could create elaborately decorated glass vases, cups, bowls and chandeliers that would be exciting to look at and interesting to touch. He wanted to make them using the hands and experience of the best glassmakers, right in the glassworks, without any preparatory sketches. In the Ajeto glassworks, useful glass objects were brought into existence that were intended to be enjoyed by their owners.

Up until Václav Havel’s passing in 2011, he and Bořek Šípek were the best of friends. Šípek was able to formulate Havel’s general thoughts into the so-called “Modern Baroque” style which respected history while reflecting contemporary emotions. Šípek prematurely died of cancer a mere five years after Havel at the age of 66.

“I wanted my things to be functional, not to be boring, not to lose their attraction easily, and I wanted the user to slowly and gradually find unobvious qualities, little peculiarities and pleasant surprises in them.” Ivan Kubela, the artist’s chief glassmaker, recalls how unorthodox Šípek’s management was. “He was a man of extremes, either it would fall or it wouldn’t fall, it would break… When something did fall and break, we took it, put it back together and it was perfect.”

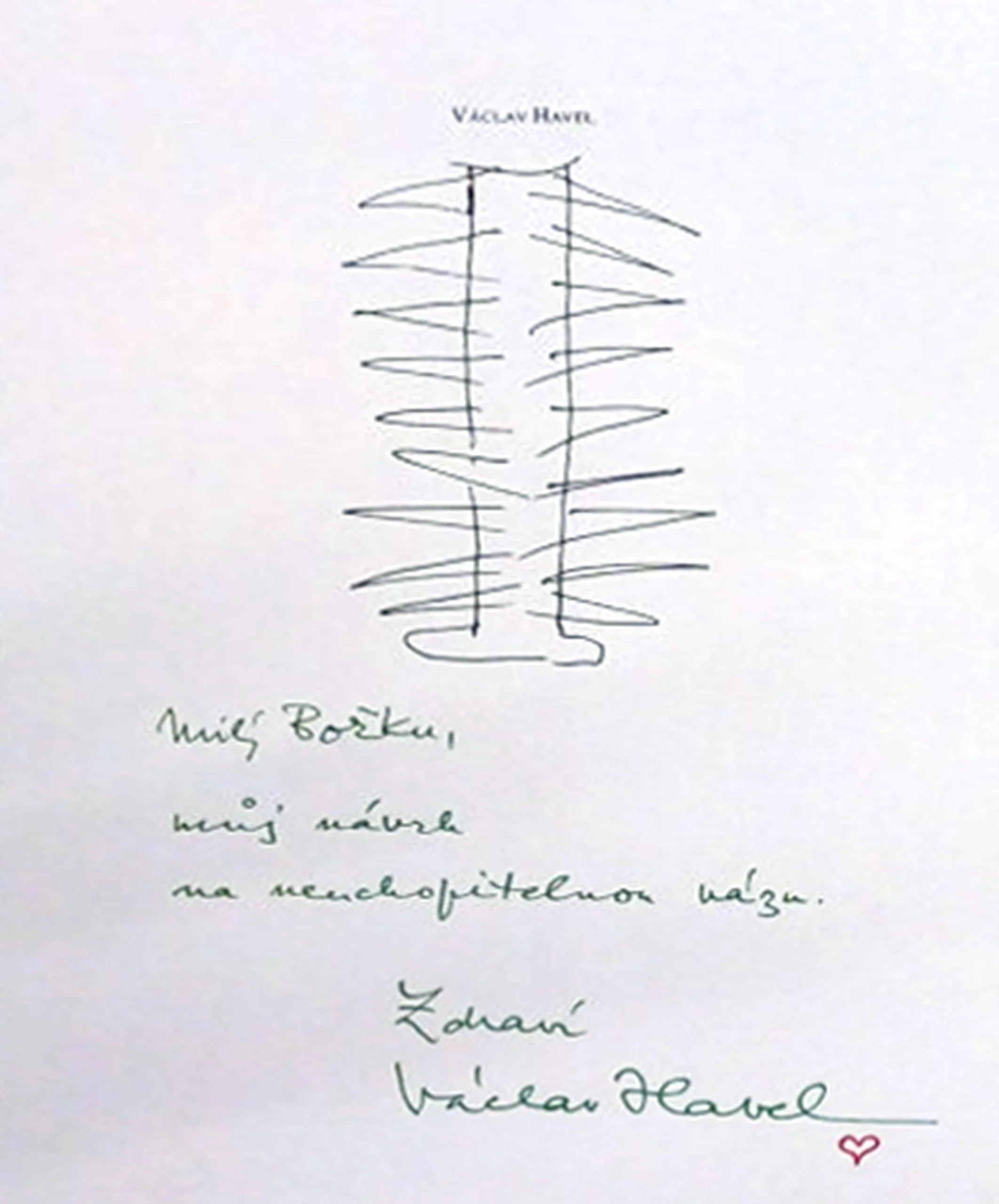

Bořek Šípek and Václav Havel were united not only by their collaboration at Prague Castle, but also by friendship. For Šípek’s 55th birthday, Havel gave him a drawing of a vase that was supposed to characterize him. “Dear Bořek, my proposal for an elusive vase,” added Havel.

Today, in the attic of the Ajeto glassworks in the North Bohemian village of Lindava, there is an archive of glass objects that were created there during the period of more than 25 years under Šípek’s direction. On display are Šípek’s original glass pieces, designs for Driade or Rosenthal, as well as the Czech theatre award of Thalia. The glassworks is currently managed by Lasvit, for which Šípek designed the Galaxy Lumina series of chandeliers, combining his interest in history with his passion for blown glass, and the Prato di Fiori lighting fixture inspired by a flowering mountain meadow.

Sources: Dagmar Sedlická, Fenomén Šípek, Mladá Fronta, 2008 Alexander von Vegesack, Bořek Šípek: die Nähe der Ferne Architektur-design, Vitra Design Museum, 1992 Milena Lamarová and Mel Byars, Borek Sipek: The nearness of far — architecture and design, Steltman and Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, 1993

“Design is not a path to a goal, but an art of moving the goal forward.”

The transparent Isotta bowl, which Šípek designed for the Italian brand Driade in 1991, was inspired by unbridled fantasy and the Baroque. It is decorated by coloured leaves.

The Ajeto glassworks also produced a small collection of vases designed by Václav Havel. Havel, originally a playwright, ingeniously used the Czech meaning of Šípek’s surname (šípek = dog rose) to express how he perceived the personality of Bořek Šípek. His drawing, entitled The Elusive Vase, depicted the twig of prickly wild rose studded with thorns.

Created on the basis of the drawing, the vase made of Czech lead crystal glass has a similar shape – large thorns cover the entire surface of the vessel in the shape of a cylinder. In recapitulating many aspects of Šípek’s work and life, it becomes clear how fitting the adjective “elusive” that Václav Havel used was. Nonetheless, what is also evident is that Bořek Šípek’s oeuvre actually defies all adjectives.

Czech architect and designer Bořek Šípek (1949–2016) is world-renowned artists. He collaborated with well-known companies such as Alessi, Driade, Lasvit, Leitner, Rosenthal, Scarabas, Sèvres, Steltman, Vitra, etc. and received many international awards. Between 1990 and 2003 he served as chief architect of Prague Castle and in 1991, he co-founded the Ajeto glassworks. Bořek Šípek’s works of art are part of the collections of prestigious museums around the world and belong among the favorite collector’s objects.