Glass Is Constant Change, Never Still, or You'll Perish

By: Eva Slunečková

Photo: Shotby.us

“There is nothing permanent except change.”

Heraclitus

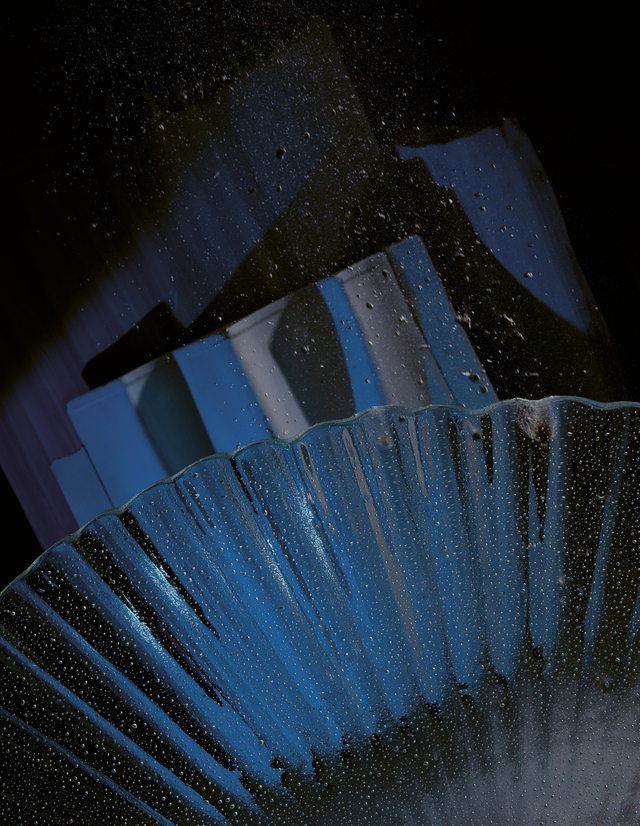

Unique fused glass technology

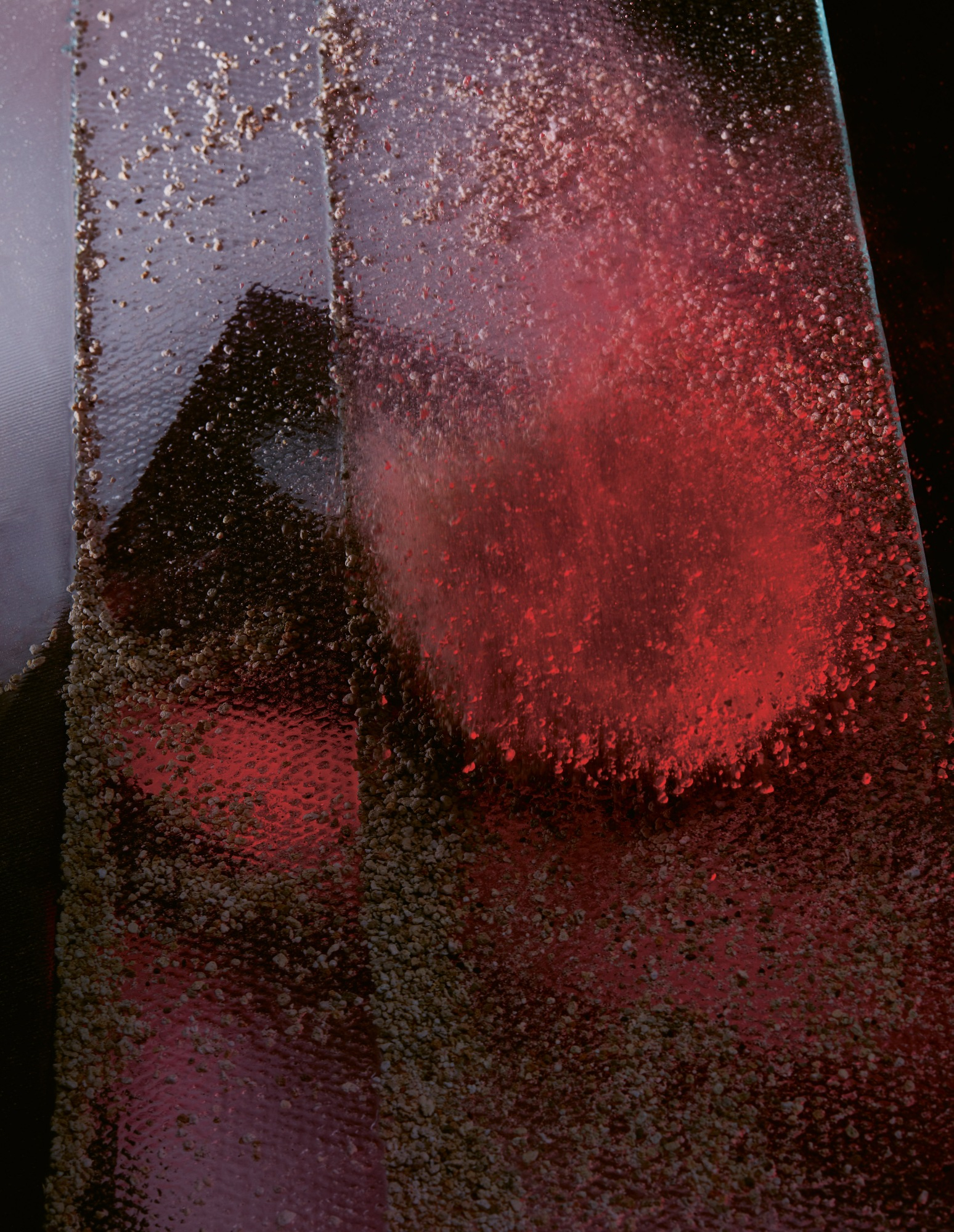

Somewhere between 500 and 600 degrees Celsius, glass quietly reaches the point of transfor-mation. “An experienced glassmaker will recognize this moment based on experience and careful notes he has been taking for several years. You have to have a feel for it,” says Jaroslav Švácha, who has been involved in the field of fused glass technology throughout his career. In contrast to the glassblowing at the glassworks, the fused glass is about working patiently with tables, numbers, and precise data. “What glassblow¬ers can’t do with their blowpipes, we can produce in the fused glass furnace. Using a blowpipe, you can make an object that is maximum fifty centimetres in size. More than six¬ty centimetres, it’s up to us,” he adds.

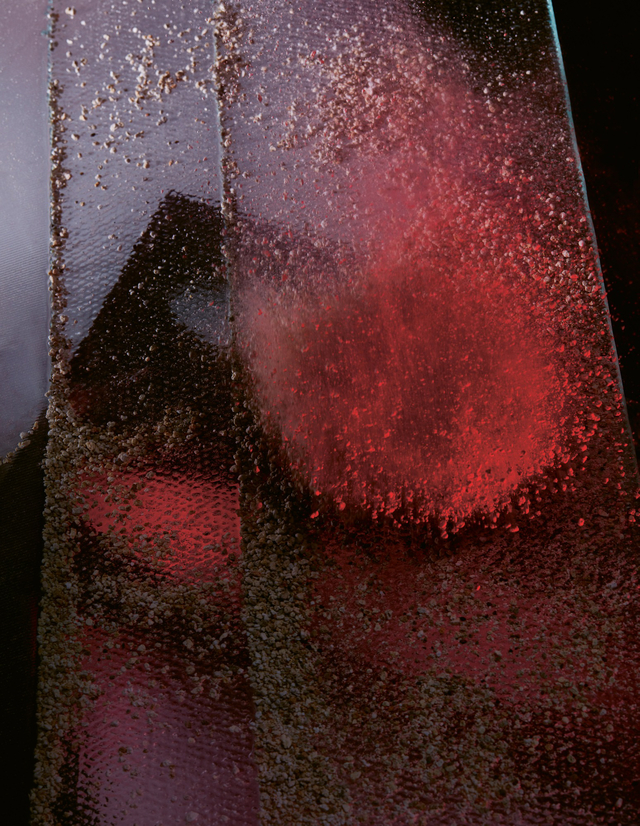

World's largest glass furnace

Right now, his colleague is making large sheets of glass for the interior of the renovated Fairmont Golden Prague hotel. The glass sheets have been in production for a month, in the largest of the eighteen furnaces in the glassworks. This jumbo furnace is one of a kind. It is one of the few in the world where it is possible to produce items in giant sizes, up to three by six metres. To give you an idea: if the sheets were placed next to each other, they would cover an area of one thousand square metres. These are such large pieces that they cannot be moved by people and require the use of a crane. Designers often work with a large number of small pieces, which the belt furnace a little way further can manage like the intended production of artisanal glass facades for EXPO 2025 in Osaka is currently being prepared a short way off.

Toward the artwork

In contrast to glassblowing, the fused glass process makes it possible to achieve more precise thicknesses and large surfaces on which the artists can imprint their imagination. In some projects, this is literally the case, as with the largest sculpture by Lasvit in Europe. The lighting fixture in Bořislavka, Prague, consists of a hundred glass panels, including one with actual imprints of the hands of the building owners and the designer and artistic director of Lasvit, Maxim Velčovský. One of the critical tests that flat glass from Švácha’s glassworks has undergone so far, and was met with an enthusiastic response worldwide, was the glass facade of the Lasvit headquarters in Nový Bor in the north of the Czech Republic. It required innovative work with materials – from processing to adjustment, all the way to high demands on the durability of surfaces.

Glass is a seismograph of social climate

Why is it that artists from all over the world regularly come to glassworks in the heart of Europe? One of the reasons is undoubtedly the affordable price and skills of local craftsmen, but the most crucial factor is flexibility – the willingness to adapt and learn new things. “We constantly educate ourselves, experiment, and push the boundaries of what glass is capable of. Craftsmanship simply cannot do without it,” says David Ševčík, the director of Ajeto glassworks, which is part of the Lasvit group. There are, however, dozens of similar, larger and smaller glassworks and studios in the nearby area. The Czech Republic is one of the last countries where several centuries-old glassmaking traditions still thrive.

The glass Superpower called Bohemia

Since the modern era, the Czech lands have ranked among glassmaking powerhouses. In the late 17th century, the world-famous Czech crystal emerged, and in 1712, the longest operating glassworks in the world in Harrachov was established. Over time, Czech glass became known all over the world. However, events in the past show that this itself does not guarantee everlasting success. The situation after World War II had a major impact on the development of glassworks. It was only after the Velvet Revolution in 1989 that long-term mismanagement came to light. Although foreign markets opened up for handmade glass, and it seemed that they could not get enough of it, the euphoria was temporary. “I’m convinced that if Lasvit, with its new approach to glass had not been established in 2007, most of the glassworks in Nový Bor would probably no longer exist today,” says David Ševčík.

People are still the same

While the function of glass has indeed changed over time, the skills of local crafts¬men have not. Only their numbers have. In the 1990s, the glassmaking complex located in Nový Bor was the largest in the world, employing nearly seven thousand people. Today, approximately a thousand craftsmen make their living in glassmaking. It is slowly becoming a dying craft, and its value increases with each aging glassmaker.

Neverending journey

Crises repeatedly reveal the true and rather unforgiving nature of glass, but also its potential. After months of wild fluctuations at the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the price of gas eventually stabilized at twice the original cost per kilowatt-hour. Even for this, fused glass has an answer. Because glass furnaces require precise control, they are powered by electricity, the price of which, in the long term, withstands crises better than gas. The variety of differently sized facilities also allow for maximum efficiency in the use of energy. Glass can be quite foxy, but it will not easily outsmart experienced glassmakers from North Bohemia!